Fall 2023

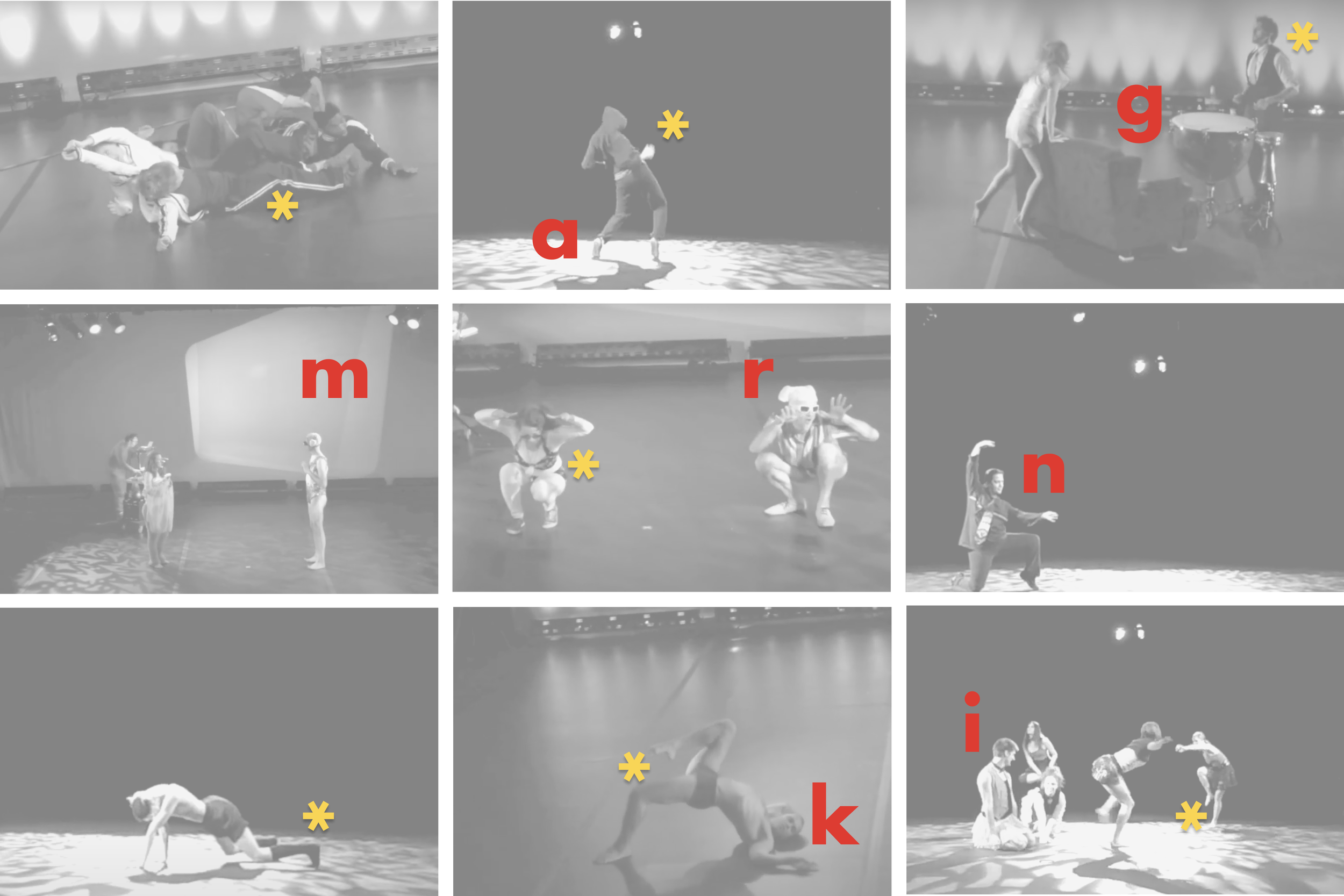

Stills from Dance Carousel 2010 and 2012 videos owned by Ellen Bartel, shot by Tom Machalek (2010) and Patrick McGarrigle (2012).

hi

This is Marking

I look through the dance sections of my bookshelves for inspiration of what to call this thing.

Those books document so many attempts at naming the source of the phenomenon we call dance: spirit, muse, chance, vision, wonder. There are names for what people do when they create dances: choreography, habit, dancing, moving, inquiry, exploring, making, creating. There are names for the result: dances, works, happenings, performances, THE dance. And there are metaphors: the theatrical (Mirrors and Scrims), the spiritual (Howling Near Heaven), the cheeky (Terpsichore in Sneakers).

What I’m interested in is how dancers and movers experience life and investigate embodied humanity. This work they (you) do to explore our physical and somatic worlds is more important than ever today, when virtual experiences are sold to us as though they are real or better than embodied ones.

When we mark steps, it’s to groove them into our bodies, or it’s to work something out, or it’s to communicate something to others. When we take a note or sketch an idea in letterforms or pixels, it’s to groove something into conscious memory. While full out is performative, marking is a process by which we communicate with ourselves and with each other.

The grooves we make by marking (if not the pixels or the paper) seem to last. ✱

essay

Coming back around

What Dance Carousel holds.

“It’s not even really about dance,” says Ellen Bartel about Dance Carousel, the concert-challenge-minifestival she founded in 2004.

“It’s about this process we have of bringing people together. It’s like kids going, you want to see my room? It’s one moment inside the big Thanksgiving dinner.”

The Thanksgiving dinner—a Friendsgiving of Austin-based choreographers—is back this year after a pause of over a decade. The rules of performance have always been the same: Each of 10 choreographers gets a total of four minutes of stage time, presented in a round of 60-second dances. Entrances and exits need to be as quick as possible. The idea is that the ride doesn’t stop till the 40 minutes are over.

Technically, each of the choreographic voices takes four singular turns. But as an audience member, the experience is like this: by the third or fourth round, the voices become clear and familiar, both individually and in the way they exist among the others, like when a song on a mixtape is colored by your knowledge, from repeated listening, of which song comes next.

After producing Dance Carousel for nine years in a row, by 2012, Ellen had it down: She knew how to fairly draw applicant names out of a hat to determine the program. She knew how to communicate the requirements to the choreographers. And she knew how to keep them from drawing out entrances and exits to eke out more than their allotted time. For years, Ellen’s husband, Dave, a guitarist and college math teacher, compiled the sound onto CD—a fugue of recorded tracks and, for pieces with live music or silence, bell cues to mark the time—and that sound propelled the show. Dave died at the end of 2012, and Dance Carousel, among other things, stopped.

This year, Ellen and four coproducers—Emily Rushing, Rosalyn Nasky, Lisa Anne Kobdish, and Alexa Capareda, who were all in their 20s in 2012—are bringing it back. Sound and lighting designer Stephen Pruitt will keep the time. There will be two programs, to accommodate 20 choreographers in all. Two fundraisers are paying the bills and choreographers. Finally, there is no hat. Ellen and the coproducers collaboratively curated the programs to give space to established and emerging artists they admire, including each other.

At Dance Carousel 2004, choreographer Caroline Sutton Clark presented dances for a quintet, including herself, who all happened to be pregnant. The next year, the same dancers performed with their babies. Even as its place on the calendar shifted from year to year, Dance Carousel was a ritual for the community. It marked time.

When I met Ellen in 2008, Dance Carousel was in its fifth year. Her eight-year-old Spank Dance Company was about to produce the first Big Range Austin Dance Festival, a two-weekend event based loosely on a sister festival in Houston.

For nearly a decade, Ellen had managed her own space for class and rehearsals, the downtown Center Studio, until it burned down in 2006. She also created, with Allison Orr, the Austin Independent Choreographers community of practice, whose email list is where I first heard about many dance happenings. Finally, she was a drummer, with Dave on guitar, for a Tom Waits tribute band, the Boxspring Hogs.

This is all to say, she was driven and productive. But she was also focused, patient, meditative. Her first dance company was a slow-motion group called The Creeps (1995–2000), an incubator for her ongoing relationship with butoh-influenced performance. With a small group of musicians and dancers, she gave regular butoh performances in the 2000s, including on a dedicated program at Big Range.

Butoh-ka is tattooed down the length of one of Ellen’s forearms. Dave is tattooed on the other.

Ellen and Caroline Sutton Clark in butoh performance, at David Ohlerking’s Austin Figurative Gallery, around 2005. Photo by David Glen Robinson.

Ellen’s memoir, Tales of a Gen X Nobody: An Evolution of Performance Art in Post "Slacker" Era Austin, Texas, self-published earlier this month, reflects on her experiences as an artist embedded in Austin’s modern dance, performance, and live music scenes over a 30-year period, starting in the mid-1990s. As a historical document and artist’s archive, it’s fascinating. Details like a $7 dispute over unpaid rent for the use of her downtown studio and celebrity cameos at Little City café, where she worked to pay the bills, are historically revealing. Her recollections of what it felt like to create and perform, like in near-death experiences in butoh, serve as a portal to her idiosyncratic embodied experience.

The book also documents the trauma of Dave’s illness and death. Interwoven throughout—the structure is often at the mercy of memory and other phenomena that circle back, a reminder that nothing, not even chronology, is actually linear—is the mindfuck of what happened to her career after 2012.

Ellen holds a production meeting in her living room.

Alexa, Emily, and Stephen Pruitt sit on a shag-pile rug, in the center of which someone has placed a plate of red grapes. Ellen points out a taped-up rectangle of dark material over one spot on the ceiling. The A/C is leaking, and as it’s Sunday evening, she’s waiting until the morning to call a plumber. There’s an occasional drip in the background as the conversation moves to a press release that Alexa, who’s in charge of publicity, has drafted.

The WHAT and WHEN lines are straightforward—they’ve all locked in the dates, with the Ground Floor Theatre and their own busy schedules, a year ago. But WHO gives them pause.

The coproducers are all Austin independent choreographers, in the general sense, but are they Austin Independent Choreographers, the proper name of the community-of-practice group from the first decade of the 2000s? “People might be like, oh, you’re starting it up again? When are we meeting?” Ellen, not quick to laugh, smiles. It’s OK to use the name, she says.

Next, they discuss photos, the currency of media coverage. Photos from before 2012 won’t cut it—they’re just snapshots. They could shoot rehearsal photos, if only people were going to start rehearsing in time. Lisa couldn’t make the meeting, but later, she tells me about her own efficient process with her collaborator: “We’ve been exchanging ideas in texts—we’re probably going to rehearse twice.” These are the lessons of the pandemic: Do as much as you can apart, before going in to the studio.

They also go over tasks and deadlines for the choreographers—submit photo, bio, music—so Emily, in charge of artist communications, can relay them in emails. Ellen has printed out calendars on which everyone can mark important dates. Ellen and Alexa are both teachers, beholden to the academic calendar. As the dates push into September, they utter sounds of stress.

Emily has misplaced her paper calendar and takes notes on her phone instead. “I’m not texting,” she tells Ellen, a bit nervously. “I know,” nods Ellen.

In June 2012, after a long Dance Carousel tech rehearsal, Ellen took Dave to the emergency room, where he was diagnosed with cancer. From that point on, the dominos of her life clattered away in an unknown direction as she became a full-time caregiver, and then a widow.

To the testament of the community, Dance Carousel, short one choreographer, and the rest of Big Range, minus the butoh program, went on without Ellen. She spent the rest of the summer driving back and forth between her home and the hospital.

The movement she was most concerned with during that time was whether Dave could move his legs (as tumors pressed on his spine, he soon could not). The body she was concerned with was his. Her own movement rituals surfaced only as tools to use in crisis, like sun salutations performed in a hospital waiting room, she recalls in her book, “just to calm the fuck down.”

In her book, Ellen describes having to return creative funding from the city, and the moment when she realized she could not, would not, apply for it, as she had done for the previous 12 years, ever again. She writes that her quick and firm decision surprised herself—it was an act of instinctive self-protection against the pain of having to pull together documentation from the year Dave became sick, and the domino years after that.

Rather than try to keep up with a cycle that no longer made sense in her life, Ellen walked away from trying to fund her work.

When Dance Carousel, Big Range, and the other operations of Spank Dance Company ended, in 2012, they did so indefinitely, with neither a promise of return nor closure. Talks Ellen had been part of about opening a studio—a dream she’d had since losing Center Studio—went on without her. Over time, much of the space in the dance community that she had taken up, or stewarded for others, became filled, or simply closed.

“That’s the ambiguous grief,” she says. From her book:

Neither me nor the dance community ever said goodbye to Spank Dance Company. It’s probably the same grief that comes with Austin’s shifting landscape. We have no closure when builders eviscerate our architectural history from our neighborhoods. And the same came with losing my identify as a wife, no one prepared me.

Ellen didn’t disappear from Austin’s independent dance scene. Over the past decade, she has presented work in shows produced by others, danced in friends’ work, and taught dance at Austin Community College. She also completed studies at the Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies, becoming a Certified Movement Analyst and Registered Somatic Movement Educator. She then established the 560-hour Somatic Movement Education Training program at ACC and started a private practice, Austin Somatic Movement Education.

Through ASME, her offerings include private grief processing sessions.

Meanwhile, the voices of Lisa, Alexa, Emily, and Rosalyn emerged as part of a mixtape, eclectic but directional.

Lisa joined Kathy Dunn Hamrick Dance company and helped produce Austin Dance Festival, which launched in 2017. Alexa became the rehearsal director for Ballet Austin’s apprentice company and trainee program, choreographing for them, too, and developing her solo practice. Rosalyn continued her work with experimental musicians, creating performances for Monkeytown and Fusebox Festival, and began a long-term collaboration with Heloise Gold.

Emily, with collaborators Yvonne Keyrouz, Judd Farris, and her husband, Cody Rushing, produced Seam Project, a series of backyard performances on a four-foot-square platform. Along with Seam, two other initiatives produced regular, collaborative performance during the second half of the 2010s: 11:11 (2016–17), produced by Jennifer Sherburn, was a monthly series of commisioned performances in beautifully designed event spaces. Studio Series Show (2018–19), was a series of work-in-progress showings inside producer Kirstan Clifford’s apartment and, later, on an outdoor, makeshift stage.

While I’m glossing over many other important influences, these three had in common a spirit of momentous collaboration, with each event offering a curated experience of performance, live music, and design (plus, often, a signature cocktail). The result was a brightness, an invigoration, in both artists and audiences.

“It’s nice when the majority of the crowd is people you don’t know,” says Emily. At the first Seam performance in an East side backyard, an audience of 90, both artist-adjacent and neighbors, squeezed in.

Emily Rushing in 2020. Photo by Jose Saldivar.

And then we all learned about ambiguous grief. During the pandemic, everyone, and especially performing artists, dealt with the the loss of events that would never happen, halted momentum, and dissipation of possibility.

For Emily, 2020 began as a shift into new ventures after spending more than a year focused on Seam. ”There were so many things we had started to line up, and it all sort of dissolved,” she recalls. She isolated herself perhaps even more than some of her colleagues, to help protect a family member particularly vulnerable to Covid. “I was very creatively slumped, and I started to get apathetic toward dance in general.”

For Ellen, the pandemic was another domino, an isolated clack among the life she had worked hard to rebuild. The pandemic amplified increasing costs of living, especially housing costs, in Austin. Over the past few years, the property tax bill for Ellen’s home, where she moved after Dave died, has increased to the point where the math is nearly impossible.

In May 2012, Ellen was about to graduate with an MFA from the University of Texas, so I interviewed her for a Chronicle piece about her plans. I worried that now that Ellen was academically credentialed, she would leave Austin for a stable, benefits-offering university teaching job elsewhere. No, she said, according to my interview notes. “I’m happily married, and we own this house.”

We may have been sitting in her office, in the house she shared with Dave. Dave may have walked by and said hello.

“And, Austin’s beautiful. . . . So I’m putting my energy into my company.”

I haven’t recalled that interview yet, in mid-September. I’m sitting with Ellen, outside in the heat, just across Interstate 35 from where Center Studio once stood, surrounded by fresh concrete and construction signs, across from a shoddy metal garage where pedicab drivers cycled in and out, the lights on their carriages blinking.

“It never became what I thought it was going to be.” We’re talking about her company and loss.

“It’s emotional, not artistic. I wanted a space, a dance company, and a regular season.”

“I’ve been searching for a regular something my whole life.” Her voice has equal parts incredulity and resignation. There’s some silence. “I’ve been gigging it.”

The shape of this loss, like the space left for her in the dance community after she paused to take care of Dave and her resulting trauma, is irregular. It’s shaped by the roll of the dice that made her a caregiver when a new era of her work was just about start.

It’s shaped by the increasing difficulty of living on a working artist’s income in Austin, and by the fact that Austin has long been a never-grow-up city—even as it has gotten richer and richer, it has kept its Peter Pan repudiation of seriousness—that turns its back on older and established artists, especially dance artists, and especially women.

At Austin Dance Festival 2019, Ellen presented a work for fourteen women. (I missed it, but Ellen describes it in her book, and a rehearsal video is on YouTube.) The performers wear business suits and are burdened by handbags. The sound is industrial. They begin in butoh-like slow movement and end by wiping imaginary spots from the floor where they stood before going offstage.

The title of the work is “Stagnation: When Is It My Turn, Bitch?”

Ellen in her Center Studio, late 1990s. Photo by Cindy Light.

Emily, who struggled to find purpose during the pandemic, is rejuvenated now.

She’s working on a business plan to support her objective of having her own company and running a studio and performance space. She views Ellen as a mentor and, as a college student, attended her butoh shows. A Texas native who studied dance at Austin Community College and the University of Texas, Emily is effortlessly cool. When she springs into movement, it’s like, oh, you thought I was just chilling here—you had no idea. Her intensity is of a completely different timbre than Ellen’s. Nevertheless, she says, “I feel like we relate.”

Emily is trying not to let Austin’s commercial real estate prices deflate her goals. Producing a year of outdoor shows in backyards made her an expert on their limitations: light and sound are hard to do well outside with budget equipment, and performers get tired of dealing with heat, cold, humidity, and bugs. “We’re all scrappy in that way. We’ll make it work,” she says. But she’s hoping that her relative financial stability—her partner, Cody, does lighting and sound design but also has a stable technology job—will help her create a solution.

More than anything, Emily thrives in collaborating and finding ways to support others’ work. One of the best parts about Seam Project, she says, was simply “using the resources we have and sharing them.” She likes the inquiry of a constraint. “The beauty of a one-minute piece,” she says, for example, “is that it lends itself to comedy somehow. Not always, but it keeps the audience curious.”

Ellen is mostly busy overseeing the production, plus rehearsing her one-minute dances, which are for 20 dancers, give or take. But she has also been thinking about how Dance Carousel 2023 brings an opportunity for personal closure—however that presents. “I could potentially leave that event feeling very, very sad and disappointed,” she says. Or, it could be, “Let’s have that farewell that Spank Dance Company didn’t get to have. My brain tousles between the two.”

Some of this year’s audiences won’t even know that Dance Carousel has a legacy. They may not know that we used to write about it for the newspaper and that people would read it, maybe at Little City café, and maybe they would leave the paper on the table for the next patron to read. And that maybe those who had been there would talk about it, over coffee, what they liked and didn’t like and who else was there.

That doesn’t make it any less true: Dance Carousel is a manifestation of a wish. What if, for 40 minutes a night, the community you helped give shape to could hold your space, however irregularly shaped, and your grief, however ambiguous?

✱

Go get it

Dance Carousel is October 18th–21st, 8pm, at Austin’s Ground Floor Theatre:

Program A, October 18th and 20th: Jahna Bobolia, Alexa Capareda, Mira Cook, ACC Faculty (Darla Johnson, Melissa Sanderson, Catherine Solaas), Brandon Gonzalez, Katherine Hodges, Lisa Kobdish, Taryn Lavery, Rosalyn Nasky, Kelsey Oliver.

Program B, October 19th and 21st: Ellen Bartel, Jairus Carr, Dany Casey + Errin Delperdang, Alyson Dolan, Heloise Gold, Evelyn Hoelscher, Sharon Marroquín, Anu Naimpally, Rachel Nayer, Emily Rushing.

Tickets, $25–35 (per show, sliding scale) available soon at dancecarouselaustin.com.

Follow @dancecarouselatx for more info and updates.

Contribute to their GoFundMe to pay the choreographers.

Tales of a Gen X Nobody an Evolution of Performance Art in Post "Slacker" Era Austin, Texas, paperback, 159 pages, is available for $30 + shipping at Lulu.

interlude

Six degrees

1. Teresa Taylor, Butthole Surfers drummer and Slacker cameo star, died in June. 2. In Slacker, her character was a street pusher, selling a “Madonna pap smear” in a tiny glass vial. 3. Ellen Bartel moved to Austin because of Slacker and became a self-taught drummer, starting off sets with 5-6-7-8 instead of 1-2-3-4 (from her book). 4. Madonna was a dancer before she was a singer. 5. A lot of kids in the 1980s just wanted to dance with Madonna, prompting their parents to sign them up for ballet-tap-jazz, but Madonna on TV was a lot of people’s first dance teacher. 6. The day the Slacker crew was filming Teresa’s part, she was wearing a T-shirt that read “FUCK ART LETS DANCE.” Rick Linklater had her turn it inside out—a bit too on the nose (from the Chronicle).

reflections

Postscript

This essay expanded and contracted. It began about Dance Carousel as a marker of time and change, got really big, conceptually, and then ended in the section of the Venn diagram about where and how the first theme and Ellen’s singular life intersect. Which is a big section.

When I’m writing about a person in depth, I just want to do right by them. All I want is for them to feel seen and feel like someone wrote it down for posterity, and for the piece to sound like legitimate journalism rather than gush of awe.

Writing about a group is challenging for me. I struggled to integrate the very important and equivalent perspectives and work of Alexa, Lisa, and Rosalyn. The focus on Emily emerged late in my process, and it seems now clear and right.

Will this be the last piece of journalism anyone writes about Ellen? Will there ever be another Dance Carousel?

Even if anything I write here is important, this site won’t last forever. If we’re lucky, I guess, the AI bots will absorb this with some useful logic before it goes away.

I’m really grateful to everyone who helped with this, talked with me, shared links and histories and photos—both for this piece and way before—and for the journalists of past decades. Thank you to Ellen Bartel, Alexa Capareda, Emily Rushing, Lisa Anne Kobdish, and Rosalyn Nasky for letting me land in your brilliant worlds for a bit.

Let me know how it landed for you, if you get a chance. In any case, I’ll be working on some ideas for issue 2, slated for sometime in December.

—JONELLE

✱